[This article was originally posted in 2020 on the now-gone Digital Solutions blog.]

Swapping out the database layer of an application is rarely easy. It’s even less easy when you’re also changing the storage paradigm (say, from a document database to a relational database). It’s even less easy when you run into peripheral snags. But I’ll come back to that.

At H.I. Digital Solutions (DS), we do our best to deliver a steady stream of business value. We try to limit our work-in-progress (WIP) and slice our tasks as small as we can while making sure each one delivers business value. Even so, there are some tasks (such as swapping out the database layer of an application) that are large, at least compared to our preferred slice size.

And sometimes, large tasks hit peripheral snags and become, unexpectedly, larger.

This post is a retrospective on our adventures in swapping out the database layer of an application. This task just so happened to take about ten times longer than our average cycle time. It seems worth trying to figure out what mistakes we made and what, if anything, we could have improved.

Let’s start with a bit of background on what we did, then evaluate what went well and what didn’t.

Background

My team of three engineers had been working on an application for several months. It’s an Azure Function App (serverless), written in C#, that at the time used a Cosmos DB document database.

The application does two things: Collects and Counts. Every day, it collects data from several source systems and stores them to the database. Every month, it applies some business rules to the collected data to generate a summarized count report. The amount of data isn’t terribly large—a few tens of thousands of records in each daily collection.

We had chosen Cosmos DB primarily because it scaled nicely with our serverless application. Instead of iterating over our top-level entities and the types of data we collect for each entity, we fan out and create an instance of a function for each combination of entity and type. Cosmos DB let us increase throughput so it would easily absorb all the data we could throw at it. More importantly, it would also let us scale down when the application wasn’t running, to keep costs low.

Besides scaling, our data model seemed ideal for a document database: a small number of relatively large, nested records. Cosmos DB seemed like a great fit.

The Problem

The longer we used Cosmos DB, the more minor frustrations we had with it.

For starters, Cosmos DB is billed based on throughput and time. Each hour’s bill is calculated based on the maximum throughput that had been provisioned. This application needed throughput turned up from the minimum 400 RUs to 7000 RUs. To save cost and sanity, we automatically turned up the throughput before we began, and automatically turned down the throughput when we finished. Unfortunately, that drove some less-than-ideal architectural decisions. For example, we had to collect data from all of our source systems within the same top-level Azure function. If we had independent Azure functions for each source system, one might finish collecting, turn down the throughput on Cosmos DB, and leave another function throughput-starved and getting HTTP 429 errors.

We also ran into minor annoyances with administering Cosmos DB. At the time (and maybe still), the Azure portal did not provide a way to delete or update documents in Cosmos DB. Period. If something went wrong in Production, or if we decided we needed a new mandatory field on a model, we had to jump through some hoops to fix our data.1

Besides that, we changed our data model. We moved away from using a small number of large, nested records to a large number of small, flat records. The change made our application code much cleaner, but meant our data wasn’t as ideal for Cosmos DB. It increased our throughput needs slightly. Overall, it wasn’t a big problem; we simply weren’t in the sweet spot for a document database anymore.

Finally, we ran into limitations while using LINQ to query data in Cosmos DB. It’s not clear whether it’s the LINQ to Cosmos DB SQL translator or Cosmos DB itself that was the limiting factor. Either way, we had to modify our LINQ queries to get them to run against Cosmos DB. Most of the modifications made the queries less readable; many of them arguably made the queries less efficient. The limitation we ran into most often was lack of support for GROUP BY. We’d have to add a .AsEnumerable() call, which pulls all the queried records out of the database and into the function app, prior to applying grouping (.GroupBy()) within the function app.

Cosmos DB was workable, but definitely not ideal. Even so, we were prepared to get through the project with it, because—despite all the minor annoyances—it worked and still seemed to be the best fit for our serverless approach.

Another Solution?

In early November 2019, Microsoft announced that its serverless SQL Server offering was out of preview and into general availability. The pricing model seemed good. We especially liked the auto-pause feature. After an hour of non-use, the database would automatically pause, and we’d get billed only for storage.

It seemed that we could simply size SQL Server to our needed throughput, then let it pause (and cost us virtually nothing!) during the 23 hours per day our application wasn’t running. The small, independent records would fit nicely into rows of a relational database. And the annoyances about administering a database would vanish with the whole range of SQL queries available. Where Cosmos DB had met our requirements, it seemed Serverless SQL Server was an even better fit.

We didn’t want to get ahead of ourselves, so we wrote up a spike to answer the question “Can we use SQL Server instead of Cosmos DB?”

The Spike

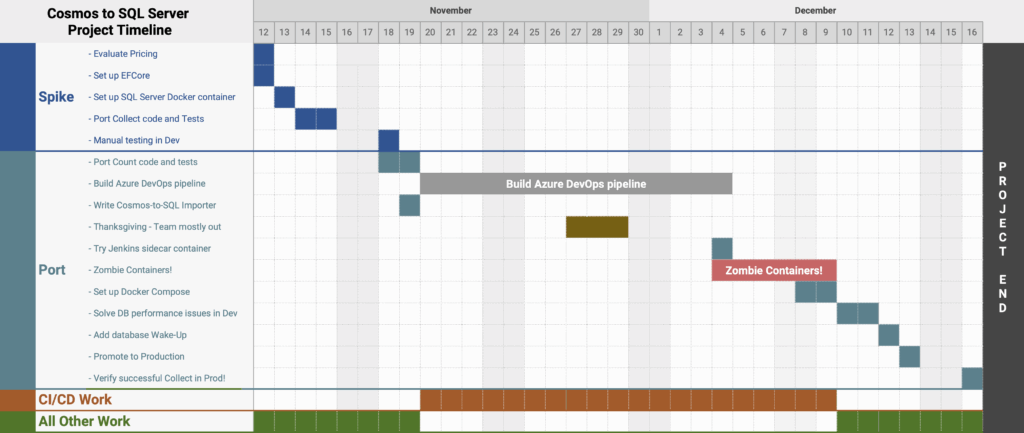

On Tuesday, November 12, 2019, we started the spike.

Answering basic questions about pricing, sizing, and connection limits went pretty quickly. Everything looked good in the documentation. That let us move on to the next step of proving out an implementation.

We decided that we’d use Entity Framework Core, so we modified our models and set up our initial database migrations. We tested the migrations using the SQL Server Docker image Microsoft so kindly provides. Everything continued to look good.

One of the most time-consuming steps was updating our acceptance tests. The Gherkin feature files had several large blocks of JSON in them representing Cosmos DB documents. We decided those should be converted to tables, because tables would better represent data in SQL Server tables. That led to a few changes in the steps file that converted the Gherkin data into our models. Besides that, we needed to start a fresh SQL Server Docker container and run the migrations to give ourselves a fresh database each time the tests were run. After the tests were modified and our scripts updated, everything continued to look good.

For our spike, we changed our Collect function to use SQL Server, but left Count alone. We expected Collect to put significantly more load on the database. Our reasoning was that collection pushed the most data into the database, and certainly had the most simultaneous clients. We thought we would learn the most about the necessary database size from Collect. After all, Count simply fans out to SELECT, fans back in, then does a few INSERTs from a single client; it should not need the database sized larger than Collect needs.

We wrapped up the spike early on Monday, November 18 after a manual test of Collect in Dev. The answer to our spike question was a resounding “Yes! We can use SQL Server instead of Cosmos DB!”

The Port

On Monday, November 18, 2019, we started to port our entire application to SQL Server. We dove into the task full of enthusiasm and energy, happy about how well the spike had gone.

It didn’t take us long to get through updating the Count function to use SQL Server, even with needing to replace a lot of JSON with tables in our Gherkin feature files. It also didn’t take long to knock out a little tool to import our Cosmos DB data into SQL Server. Life was going swell and everything was just peachy, except of course for the undeniable fact that we still needed to get everything building and deploying using continuous integration.

Continuous Integration

Before our spike, we’d been using self-hosted Jenkins as our CI solution. Our acceptance tests on Jenkins ran our application in a Docker container and used a real in-the-cloud Cosmos DB instance. We obviously needed to replace Cosmos DB with a SQL Server; we chose to use a SQL Server container to keep all our environments consistent, repeatable, and free from contention.

Fortunately, we had already seen that Jenkins supports something called “sidecar containers“. Unfortunately, they only seem to be supported using Scripted Pipeline syntax. Our Jenkinsfile used Declarative Pipeline syntax.

We had some options. DS had recently started using Azure DevOps for some projects. We kicked around the idea of Docker Compose under Jenkins or Azure DevOps. And, of course, we could move to Scripted Pipeline syntax for Jenkins. We had a long-term goal of moving to a SaaS CI/CD solution2, so after a few quick, unsuccessful experiments with adding a sidecar container to our current Jenkinsfile, we switched over to Azure DevOps. It was Thursday, November 21.

After a day or two of sorting out some permissions issues on Azure DevOps, setting up access tokens, wrapping our heads around how Azure DevOps does things, checking to see how various DS teams had set up their pipelines, and griping about how much had to be set up using the web UI instead of scripted, we were making progress. We were a bit annoyed that the cloud-hosted build agents had to rebuild our Docker images on each run3, so each time we tried the pipeline it took a minimum of 10 minutes.

The week of Thanksgiving, we were still trying to get Azure DevOps to work nicely for us. We experimented a bit with build artifacts as we worked, in hopes of speeding up our tests and of having the build outputs captured. As we made more progress, we started to notice sporadic, non-reproducible acceptance test failures that seemed timing-related. We speculated it was that the build agent VMs were probably pretty wimpy, tried increasing some timeouts in our acceptance tests, and headed off to eat turkey.4

On Monday, December 2, we spent most of the morning increasing timeouts and doing our best to eliminate anything that might cause intermittent failures. After consulting with other DS team members and recalling how much non-scriptable manual set-up was needed for an Azure DevOps project, we went back to Jenkins.

Switching over to Scripted Pipeline syntax for our Jenkinsfile didn’t take terribly long. After a bit of tinkering, we had our SQL Server sidecar container running!

And run it did. In fact, it enjoyed running so much that it wouldn’t stop running. Even shelling in and running docker stop wouldn’t stop the container. Worse, the command to stop the entire Docker service just hung. It seemed there was a zombie process inside the container that kept the container from stopping. We initially wrote it off as a fluke, but after the second or third reboot, well, we started to think it was something that needed to be fixed.

We figured we were doing something wrong. We did some research and tried a few changes to our Dockerfiles, using an init process in the zombie-prone container, and at one point I think we may have tried a chainsaw. None of it worked. We discovered there was something in the process the container ran that was somehow causing a kernel panic.5 But that only seemed to happen on our Jenkins build agent, not any of our development machines.

On Friday, December 6th, we had a discussion about whether updating the Docker version on the build agent might help. We ended the day cautiously optimistic that it might help—optimistic enough that we imported our Production data into Dev, ready to test on Monday.

As a team, we didn’t quite make it to Monday. On Sunday, December 8, one of us got antsy and tried Docker Compose with our original Declarative Pipeline. It worked great and kept the environment consistent across our development machines and the CI server.

On Monday, December 9, with a working solution to give us consistent environments, we turned back to the zombie container problem that was still lurking. As it turned out, updating Docker on the Jenkins build agent did not fix the problem. We briefly considered updating the operating system version to a newer release in the vague hope that it might somehow solve things. That seemed extreme, so we thought harder (and by thought, I mean we also dug through Stack Overflow, GitHub issues, and forum posts). As it turned out, we discovered a possible (and much less extreme) solution: switching the Jenkins storage driver from aufs to overlay2.6 We gave it a try. It was a much simpler update than we expected.

And it worked! We no longer saw zombie processes causing zombie containers! Some work days feel really good. That day was one of them.

Back to the Port!

The port to SQL Server wasn’t done, even though we were finally done detouring through CI difficulties. But it felt like we were pretty close.

After re-importing our Cosmos data into our dev environment SQL Server and an automated deployment to dev, we were ready to test. So we did.

As we tested, we discovered some performance problems when dealing with production-level amounts of data (approximately 4 million rows at that time). The biggest performance problem was that our Count queries, when run in parallel, took longer than the 30 second timeout that Serverless SQL Server allowed. We did the obvious thing and added a few indexes. It helped a little. The CPU utilization was maxed out, so we increased the number of vCores allocated to our database instance, which again helped a little. Even so, the application was right on the cusp of timing out. If everything went well, it would run successfully. If anything went wrong, queries timed out and exceptions rained down.

On Tuesday, December 10, we had our standing weekly project demo. We fielded some quite-justified questions about whether we were doing the right thing, whether SQL Server was the right answer, and if we should just cut our losses. Great, great questions. It had been four weeks, after all. We agreed on a short timebox for getting past the major problems.

Our plan was to use some of the query performance tools built into SQL Server Management Studio to understand why the queries were performing so poorly even with the indexes we’d added. It didn’t take us long to discover that Serverless SQL Server doesn’t work with the tools we had in mind.

After some searching, we discovered the Azure portal provides tools like “Query Performance Insight” that gave us an idea what the problematic queries were. We poked and prodded the queries, looked at execution plans, and figured out that we needed a composite index. After adding that one composite index, we were able to dial back our vCores and still peak at less than 25% CPU utilization.

There was just one small problem left. Serverless SQL Server pauses after an hour of inactivity, which is great for billing. It didn’t take long to discover that our nightly Collection run would fail because the database was paused when our application attempted to connect, and the database wouldn’t wake up before the maximum timeout was exceeded.

Waking up the database was a pretty easy problem to fix. The hardest part of the fix was waiting for the database to pause so we could test the fix.

On Friday, December 13, we did another — what we hoped was the final — import of production Cosmos data into dev. A few test runs confirmed that Collection worked great. We imported production Cosmos data into our production SQL Server instance, deployed our software to production, and waited for our scheduled weekend runs. And, of course, tried to ignore the fact it was Friday the 13th.

On Monday, December 16, the first thing we did was to check for any failures. Zero failures. Then we checked that records had indeed been collected. They had!

It had been 35 calendar days from starting the spike to finishing the port, about 23 business days,7 with four days allocated to the spike. Our typical cycle time is closer to 2.5 days.

But we were done, finally having delivered valuable software, and definitely ready to move on to the next task.

Evaluation

In this section, I’ll look at a few of the things we could have done differently. Before I do, I’m going to remind myself of a few useful facts about retrospection:

- The past has already happened. It can’t be changed. Only future behavior can be changed.8

- Projects—even software projects staffed by experienced engineers—involve learning. It’s easy to look back at what happened, and decide it would have been easy to cut out everything that wasn’t on a straight line to the goal. Doing that ignores the learning that had to happen on the way.

- Everything we did during the project seemed like the right thing to do at the time. The team might have had different opinions, or said “wow, that was a mistake”. But there was nothing we did that seemed like the wrong thing to do at the time. That said, we tried our best to recognize when we needed to change direction.

- The point of retrospection is future improvement. Identifying future behaviors or approaches is much more useful than vague suggestions like “we shoulda done that better, uh, somehow.”

Focus

One of the places that we could have improved is in our focus. Put another way, we could have been more intentional about deferring work or pausing an unproductive approach.

The biggest example of this is our Continuous Integration subtask. Continuous Integration and automated deployment are table stakes at DS; we couldn’t have reasonably cut those out of scope. Even so, we spent much longer on the CI portion than we probably should have — roughly half of the total duration was spent on CI work!

A naive Gantt chart retrospective approach would be to declare all of our Azure DevOps time wasted, our early Jenkins experiments wasted, and to suggest that we should have simply jumped straight to fixing Jenkins and using Docker Compose. While that may have been faster, that relies on knowing what worked and what didn’t.

Instead of focusing our time by knowing the right answers from the outset, I have three more realistic thoughts about ways we could have improved our focus in the moment.

First, we could have focused our attention and experimentation by giving ourselves better defined success criteria than “we should get Continuous Integration working for this project”. As we went through the subtask, we found ourselves articulating criteria like speed and repeatability — things we’d assumed but not stated. The success criteria would have helped determine what to do, and what not to do. For example, we spent some amount of time trying to figure out the “right” or “best” way to implement an Azure DevOps pipeline, including things like creating build artifacts. That took time when we hadn’t quite figured out whether Azure DevOps would even work. We could have skipped that step, at least initially. On the other hand, if we’d had speed as a criterion, we could have experimented on speeding up our Azure DevOps pipeline and maybe dropped it as a potential solution a few days earlier.

- Already Implemented: We have started using more detailed checklists on our Trello cards to help us articulate, to ourselves, the criteria we are after.

- Next Time: When dealing with larger subtasks (e.g. CI), I will task the team to take a few minutes, identify our criteria, and capture those criteria in a checklist for that subtask.

Second, we could have focused ourselves on iteration by experimenting faster. Our CI process for this project takes about ten minutes to run when it’s got a tailwind. That means each time we needed to try something different, we needed to wait ten-plus minutes — more on Azure DevOps with the Docker build times.9 We very easily could have modified the process to temporarily skip steps to make the overall process run more quickly. Or we could have created a minimal skeleton project to work out our CI process, then apply what we’d learned to our real project.

- Already Implemented: We removed several acceptance tests that were redundant with other acceptance tests. We removed others after writing unit tests to cover the functionality they tested. Removing those acceptance tests shaved 3-5 minutes off each test run.

- Next Time: When tests or other automated processes start feeling long, I will step aside from my typical willingness to “just get through this; we’re getting close to done” and have the discussion about how we can iterate faster. After all, if the CI process takes ten minutes, that should be plenty to start the discussion.

Third, we could have regularly reminded ourselves of our goal and been more aggressive at discussing options. It’s terribly easy to lose focus on the larger goals when working out a technical issue. I won’t speak for anyone else, but I’ve been known to let a technical issue with a solution make me forget to ask if there’s another solution that might be reasonable to try. We found ourselves in that place with both the Jenkins “sidecar” approach and the Azure DevOps approach. There’s no guarantee that reminding ourselves “we’re trying to get CI working so we can build and deploy our project” would have helped, but it could have led us to ask “are we doing the right thing, and are there other options we should be considering?” Or to look at another part of the project, reminding ourselves that our goal was to run our application on a realistic set of data — especially when we hit CI issues — could have led us to ask if there was a way to test performance before we got CI working.

- Next Time: I will pause to articulate a goal for subtasks, and how they fit into the overall task. Then, at work transitions (e.g. when a team member needs to go to a meeting, or when picking up for the day), I will re-state the goal. I will use that as a prompt to ask if we are working on something that seems to fit into that goal, or if we are off track.

Timeboxing

In many ways, timeboxing and focus complement each other. Limiting the time available to overcome (or at least make tangible progress on) an issue helps to focus an issue. If we had given ourselves a timebox for each set of experiments, with the intention of pulling back to look at our broader goals after the timebox, we would most likely have gotten to a solution faster.

Timeboxing would not necessarily have been just a way to cut off fruitless experimentation earlier. It might have helped us to put adequate time into a more fruitful path earlier. Were “a few quick, unsuccessful experiments with adding a sidecar container” enough? Maybe. I mentioned earlier that we had a long-term goal of moving away from that Jenkins server to a SaaS CI/CD solution. Appropriately enough, the main reason for wanting to move away from that Jenkins server was to avoid having to maintain it: updating Docker, troubleshooting Docker filesystem issues, coordinating reboots when a container turned into a zombie. Ironically, the desire to save time on server maintenance led us to “waste” time investigating Azure DevOps.10 It’s interesting to look back on the project and wonder what we might have discovered if we had given ourselves a timebox for experimentation with the sidecar. Would we have skipped our foray into Azure DevOps? Would our experiments with Azure DevOps have been better focused?

- Next Time: When dealing with a task that involves trial and error or experimentation, I will ask the team if a timebox would be appropriate. Depending on the task, the purpose of the timebox is to give us adequate time to learn, or prompt us to reconsider an approach before it goes on too long.

Minimize Effort

As a team, we want to do good work. All things being equal, we’d prefer to deliver a well-crafted solution over a, well, crufty solution.

Sometimes, that bites us.

I already discussed earlier that we spent some amount of time trying to understand how to implement our Azure DevOps pipeline the “right” or “best” way. We learned afterwards that the resources available to our Azure DevOps build agent meant our builds would take a long time and occasionally fail our test suite. The time we spent trying to understand the “best” pipeline approach could have been used elsewhere — again, knowing what we know now.

You may have noticed while reading the background that we, several times, exported data from Cosmos DB and imported it into dev or prod, thinking we were finally almost done. It wasn’t a long process, exactly — maybe 10-15 minutes to configure and perform the export; a few minutes to configure and start the import; and an hour or so for the import to run. But each time we ran that export it took our attention away from other tasks. Now, most of the times we ran the import, we thought the project was almost done and it’d be the last time. But what if we had done the first import so we’d have data to work with, then waited to do another import until everything else worked?

After all, if we had worked to maximize the amount of work not done, we might have been able to use that focus to deliver more, or better, or faster.

The challenge, of course, is recognizing in the moment that the bit of work in progress, the bit of work that you’ll get to check off the list and feel so good about checking off, can be dropped or deferred.

- Next Time: I will ask myself three questions. (1) Does this work need to be done? (2) Does this work need to be done now? (3, if yes to 2) Does this work distract from higher-priority work?

- Technical Example: As mentioned, we used a Docker SQL Server container to keep our environments consistent and avoid resource contention. Had we asked ourselves “does this work need to be done?” we might have realized we could have stuck the same approach we did with Cosmos DB: have an instance of SQL Server running in Azure that we use from all our environments, that we clean up after our tests run. Perfect? Nope. Would it have saved us immediately having to mess with sidecars, Docker Compose, and fix Jenkins? Yep.

Sequencing, Slicing, or Limiting Work In Progress?

One of my biggest questions about this has been whether we missed a chance to slice the work differently, or if we somehow failed to think correctly about how much work we had in progress.

Overlapping a bit with the Focus section, it’s pretty clear that trying to make sure our Azure DevOps pipeline was polished wasn’t completely needed. Arguably, that could be an extra work item creeping in while we had our main task in progress. Even more arguably, trying Azure DevOps could be considered a separate work item that could have been done as a separate spike. So perhaps our work in progress wasn’t an issue.

Could we have tried to sequence the work differently? If we had completed the Count side during the spike, we would have realized there were query performance issues that needed to be dealt with. Instead, it took several weeks to learn that. Knowing about the issues could have led to different choices — maybe discussions with the business about value, maybe exploring query performance analysis tools when a team member had some time to fill. This is an area that we have concluded could use some more care in the future.

Could we have sliced the work differently? That’s a difficult question. We want to deliver a complete, properly-built, properly-deployed, working system. So what could we have done to slice the task of switching to SQL Server better?

The conclusion I keep coming back to is that there is not much we could have done to slice the work differently. The changes we made to production code (i.e., the things our customers truly cared about) took very little time, while the CI work (i.e., a technical task and part of doing the work right) took most of the time.

If we had decided to remove the CI work from our scope, we’d have a system that was not automatically deployable, or perhaps a CI pipeline that deployed without running tests. Neither option fits with the way we want to work.

Even if we had simply tried to release the work we’d done with the Collect side during the spike, the CI work would have been exactly the same.

An Aside That May Interest Only Me

Before I wrote this, my strongly-held belief was that we had failed to control WIP or that we had sliced badly. In writing this, I have changed my mind. We may have lost focus, been insufficiently aggressive in deferring work, made mistakes in sequencing work, spent too long on tasks, or made other mistakes. My change of mind isn’t that interesting.

What is interesting is how writing this, essaying11 to lay out the strongest possible case for my original belief, led me to reconsider the facts and draw new conclusions. For me, at least, writing challenges ideas differently than discussion does: more systematically, more comprehensively, and more open-ended.

Technical Improvements

I mentioned earlier that one of the most time-consuming steps was converting blocks of Cosmos DB JSON in our acceptance tests to tables, even with regexes to help.

In our discussions, we questioned whether we had the right level of detail in our acceptance tests, especially with the implementation detail of the database type leaking out into the Gherkin. Angie Jones has a great article on keeping Gherkin at the right level of detail. We arguably were a bit too detailed in our Gherkin.

- Next Time: I will ask myself and the rest of the team if we are writing our Gherkin at the right level, or if we are letting implementation detail slip through into our Gherkin. I will question more diligently if we start including swaths of JSON or tables that are strikingly similar to our database schema.

Conclusion

Our goal was to change out the database layer of our application. The database layer change itself was surprisingly straightforward, given that we were also changing from a document database to a relational database.12 The most difficult aspects of the database layer change were in acceptance testing13 and tooling around identifying slow queries.

What made this a big project was the difficulties we had around Continuous Integration. Paradoxically, our CI issues led to an interruption of the steady stream of business value we wanted to deliver.

There are a few things we could have done around the CI piece to improve our performance: focus, timeboxing, minimizing effort. Interestingly, whether we moved to Azure DevOps or stuck with Jenkins, we had a large chunk of work to do — we just didn’t realize the Jenkins work was there. To emphasize that point: we didn’t realize how much hidden work there was due to server maintenance that had lagged. Without a separate infrastructure team, we own all our infrastructure, so there was no way to hide that work from ourselves.

Is it reasonable to expect replacing the entire database layer of an application to take about a month? There’s a lot that goes into that, but I think a lot of projects and companies would be excited about that performance. For our project and our work style, we were kind of disappointed by how long it took. The expectation of speed, combined with initial quick success, may have led us to overlook that hidden CI work. Maybe, just maybe, the expectations were as much of a snare for us as anything else was.

Some tasks are just plain large, even when sliced as small as reasonable. That said, if you have ideas of how we might have sliced this task differently to improve our ability to deliver value, all of DS would love to hear it.

- We got a lot of mileage out of Microsoft’s Data Migration Tool. We also used [Sacha Bruttin’s Cosmos DB Explorer](https://www.bruttin.com/Cosmos DBExplorer/) when we needed to delete a few individual records. When we needed to delete more records, it was usually easier to use the Data Migration Tool to export all the records we wanted to keep, delete the entire collection of records in Cosmos DB, then re-import the exported records. Like I said, some hoops to jump through. [↩]

- …and away from self-hosting that Jenkins server [↩]

- With cloud hosting the agent VMs are wiped clean each time, so the Docker cache can’t be used. [↩]

- And, at least for me, amazing sweet potatoes. [↩]

- For the non-technical that are still reading: that’s bad. [↩]

- The root cause seems to be a Linux kernel change that didn’t play nice with the aufs driver. [↩]

- Depending on how you count the days around Thanksgiving. [↩]

- If you tilt your head a bit and squint, “What Might Have Been” by Little Texas is a pretty good tutorial on retros. [↩]

- This isn’t strictly true, because if our change had to do with an early stage of the CI process, we got our results more quickly. [↩]

- It was definitely not a waste of time, because of what we learned. [↩]

- if you will pardon the pun [↩]

- this is largely due to architectural choices that isolated database use, and using bounded contexts to separate models. [↩]

- We learned a lot, like how to work more effectively with SpecFlow tables, writing SpecFlow extensions to handle custom column types, that sometimes we can use the existing column type handlers, and that it’s helpful to get rid of tests that no longer add value. [Note: SpecFlow was EOL’d at the end of 2024, and Reqnroll is the successor.] [↩]

Leave a Reply