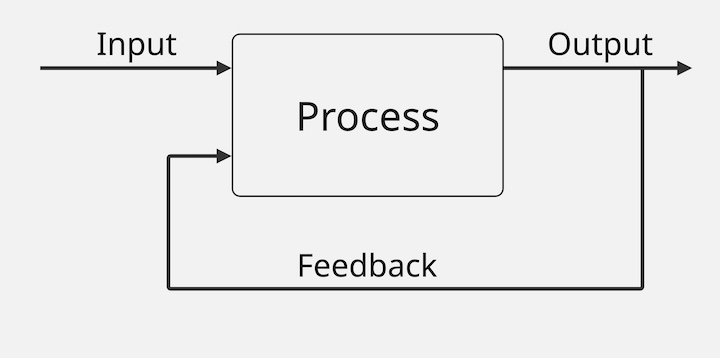

Feedback, in systems terms, is a loop that feeds outputs from a system or process back upstream as an input. As it’s more commonly used, “feedback” is information about behaviors, performance, or results1 (e.g., “don’t hit your brother”, “good hustle out there”, “our defense was almost always out of position and couldn’t get a stop”).

Feedback is generally a good thing. Without feedback, it’s difficult or impossible to respond to the world around you—as an individual or as a company. However, feedback comes with at least one drawback.

Carter Baxter recently wrote an article entitled Feedback Doesn’t Scale. It’s insightful and worth a read. (The way-too-short summary: you can’t personally get feedback from everyone as an organization scales to hundreds of people, so you’ll have to build systems to handle feedback.) While feedback is generally good, too much can be bad, because it’s overwhelming.

Feedback can be hard. You need it. Lots of it. You need to know the truth about the world outside the bounds of your skull.

This article will dig in to what happens if your company can’t handle feedback.

For people who wonder why your company can’t respond to big red warning flags being waved in front of your collective faces, this post will give a potential answer.2

For people who want to understand a bit about how to make their company more responsive to actual events, actual conditions, this post will give some ideas.

Problems with Feedback

One of the four principles of the manifesto for agile software development is “responding to change over following a plan”. Responding to change requires the ability to take in input from the outside world and from the system that does the work. In systems terms, that’s both input and feedback.3 For our purposes, we’ll lump those together as “feedback”.4

Generally, the more feedback you get, the faster and better you’ll be able to respond to events, and the better your outcomes will be. This a fairly well-known principle, and not particularly controversial.

So why is it that so many companies shy away from fast, frequent feedback?

Well, feedback is hard. It has to be gathered. It has to be understood. Even intentional sensing and feedback gathering doesn’t scale.5

All of those reasons make sense and are likely true.

There’s another reason that I’m going to spend most of this article exploring. Companies or organizations within them aren’t able to receive feedback without spiraling out of control. That’s perhaps a strong statement. A few months ago, I wrote a note to myself that led to this post.6 That note read, in part “…they aren’t able to damp the feedback. They get into spirals and uncontained runaway responses.”

Examples of Undamped Feedback

A long time ago, I got to play with the first generation Lego Mindstorms RCX controller in a group of future teachers and computer scientists. One of the first experiments we did as a group was build robots that would follow a line on the floor. We used two light sensors, one on each side of the line. If the right-hand sensor moved over the line, our robot would turn back to the right. If the left-hand sensor moved over the line, our robot would turn back to the left.

The robot needed to turn fast enough to keep the line between the sensors—otherwise it’d get completely lost. But if it turned too fast, it’d start to oscillate. The right-hand sensor would detect the line, and the robot would turn hard right. In a fraction of a second, the left-hand sensor would detect the line and it’d turn hard left. It was really funny to watch the robot bounce back and forth—right left right left right left—while hardly making any progress. It looked like it was vibrating or shaking more than driving.

Funny for a robot, not so much for a company.

The ditch on one side of the feedback road is oscillating or spiraling—re-treading the same ground over and over as feedback buffets decision-makers.

The other ditch is uncontained runaway responses.

Once upon a time, I worked with a marketing team.7 One thing web marketing teams do often is run experiments to optimize results: different page designs, different copy, different offers, etc. Experiments are an excellent way of getting feedback. But every so often, an experiment would succeed, and a person or team would leap to applying “what we learned” in other contexts, or over-applying feedback on the grounds that “if a little X is good, a lot of X must be better!”8

Damping Feedback

As Carter noted, the volume of feedback increases with the number of people involved, both inside and outside your organization.9 It can be hard to discern what feedback is accurate, what feedback is valuable, and what feedback is well-intentioned. It is even harder to figure out what feedback meets all three criteria.

Besides that, there will be contradictory feedback. The new expense reporting system is great—say some—and awful—say others. The reorg is amazing or the worst thing ever, depending on whom you ask. If you react immediately to every piece of feedback, you’ll undo and redo decisions, never making progress.

So the feedback needs to be filtered or damped.

Basic Damping

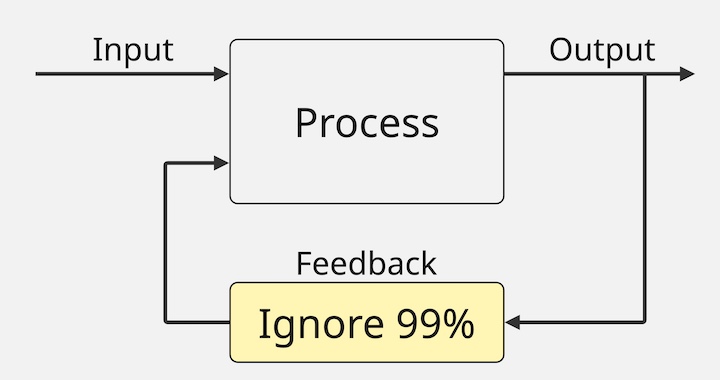

The easiest damping mechanism is to wholesale ignore most of the feedback.10

There are at least two problems with that mechanism.

First, you’re unaware of most of the feedback.

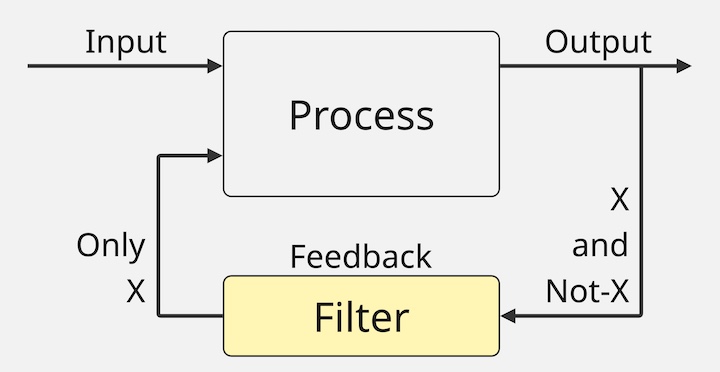

Second, feedback that makes it past the IGNORE box is acted upon with full weight. If today’s feedback is X, the direction is toward X. If tomorrow’s feedback is not-X, the direction is toward not-X.

Combining these two problems yields a third: you’re vanishingly unlikely to get an accurate picture of the world from your filtered feedback.

If your company feels like it’s always changing directions, and like the latest “new direction” gives you an eerie sense of deja vu, you’re probably right. Even if most of the feedback is being filtered out, what gets through this poor damping mechanism is causing the company direction to oscillate. Or maybe “flail around aimlessly” is more how it feels.

So you’ll move on to a better damping mechanism. What might that be? “Easy,” you say. “We’ll make sure we act on consistent feedback, so we’re not bouncing back and forth between X and not-X.”

Today’s feedback is X. Tomorrow’s feedback is also in the direction of X. And so is the feedback the day after that. You’re in an uncontained, runaway response toward X. And because of the filter you’ve built, it’s hard to detect if the environment is signaling you that you’ve gone too far in the direction of X. You simply can no longer receive not-X or less-X feedback.

In most of these situations, the leadership of the company (or department, product, etc) is genuinely trying to do their best to respond to internal and external feedback. They’re not trying to create frustration or chaos. They’re just struggling with naive feedback-handling systems.

The unfortunate consequence of naive feedback-handling systems is that feedback becomes unhelpful.

That leads to ignoring more feedback. Instead of ignoring 90% of potential feedback, that number gets cranked up to 99%, or 99.44%. Usually, this also creates a bias toward responding only to feedback coming from a source the decision-maker trusts highly or that reinforces existing plans. If you guessed this is likely to lead to runaway behavior one particular direction, you’re probably right. And if you feel like a bunch of giant flashing red warning lights are being ignored, I’d place a reasonably large bet that this is why: feedback has become a filtered, curated echo chamber.

Feedback is hard, so most of it gets thrown away, because that’s the only damping mechanism that’s been tried and found to be effective in preventing people from being overwhelmed by feedback. Whether it’s ignoring all feedback or just focusing on consistent feedback, you lose awareness of what’s going on. You can’t react with agility, because you’re not even aware of a need to react.

That’s truly not surprising. In most environments, systems to respond to feedback aren’t designed. Or actively thought about. Or generally even recognized as being a thing that one might design or think about. They just sort of happen, like so many other organizational behaviors.

Unfortunately, if most feedback gets thrown away, “you gotta holler just to be heard” if you have knowledge to drop (A. Ham), and that makes the system feel adversarial. When you’re hollering your feedback in the hope it’ll get noticed, it’s a short leap to shouting “YOU WANT THE TRUTH? YOU CAN’T HANDLE THE TRUTH!”

Better Feedback Damping

Let me offer a better way.

But first, let’s talk about springs. The sproingy metal kind, not “of cool, refreshing water”.

Think of a weight hanging from a spring.11 If you pull down on the weight and let go, it’ll bounce up and down for a good long time (that is, an undamped system with low energy loss will oscillate).

If you don’t want the weight to keep bouncing up and down on the spring for so long, you can simply reduce the energy you add to the system by not pulling the weight so far down at first. In feedback systems, that’s the equivalent of ignoring feedback.

You’re not really damping the system, but it feels that way. You’re simulating damping by reducing the energy added to the system.

Instead of simulating damping, look for ways to truly damp the feedback so you respond to events proportionally.

Do the equivalent of putting the spring and weight in a barrel of pancake syrup.12 The syrup will slow the weight down, dissipating energy as it moves, reducing the length of time the weight will bounce. (The downside is your hands will get sticky when you pull down on the weight.)

For feedback, here’s a very, very simple damping mechanism—one that I don’t think I recommend, but one that could avoid oscillation:

- Summarize and tally feedback. For example, in one week you might get 50 requests for X, 35 requests for Y, and 5 requests for not-X.

- Keep track of historical feedback, so a one-time spike doesn’t get misinterpreted as a trend. For example, if you almost always get more requests for not-X, you probably don’t want to change direction just because you get more requests for X this week.

(Obviously, this mechanism means you’d need a systematic way to gather and pre-process your feedback. That’s part of why I don’t think I recommend it.)

Here are some more useful ways to build damping into your feedback systems.

First, and most important: have a mission, vision, strategy, or North Star to come back to.13 If you know your mission is to empower people and communities through rugged, durable bicycles, you’ll be less likely to buy well-drilling equipment, even if you hear that a community needs clean, safe drinking water or access to quality healthcare.

While your mission, vision, or strategy—or, say, your project outcomes—should be fairly constant, don’t get stuck on the tactics you’re using. If your mission is to use durable bicycles to empower people, there are a lot of ways to create those bicycles. Maybe you produce them yourself. Maybe you partner with big bicycle manufacturers to build them. Maybe you ask local bike shops to build them out of excess inventory. Now, I can think of reasons each of these might not be ideal—and all those tactics and objections need to be run back through the lens of the mission. Know why you’re making the decisions you are. And be willing to pivot if needed. If you partnered with local bike shops, but can’t get the level of durability you need, it may be time to try building the bicycles yourself. If the feedback you’re gathering from yourself and your team leads you to switch databases in the middle of a project, you need to understand the reason for the pivot and be able to articulate how the change supports your strategy.

Second, delegate part of feedback gathering and summarization. Carter describes two versions of this in his article as build proxy relationships and build structured channels for feedback. If you create a working group to deal with feedback about the new expense system or the BoxyFoxPoxInSocksProxy release, high levels of the company are now insulated from unfiltered emotion and volume, and thereby protected from kneejerk reactions. People who understand the issues better will get to spend more time digesting the feedback, which damps the feedback. They’ll create recommendations, proposals, or directly fix issues.

Third, as Carter suggested, deliberately build systems to gather feedback. If you’re not the right person to architect them, delegate that task—then own the implementation. You need to own the implementation so you have skin in the game and will actually use the systems that will make feedback useful for you. The fancier your title is, the more important it is for you to have intentionally-crafted feedback systems. You can’t scale without them. And the fancier your title is, the more likely it is you’ll unintentionally react to a piece of feedback in a way that nudges the company (or at least your part of it) into an undamped response. After all, your position and fancy title amplify the feedback you choose to react to. Without systems, your chances of responding to feedback in a balanced (to say nothing of damped) way are very low.

Fourth, actively seek out contradictory feedback while you stick to your mission. You need to capture the outliers, the hints of problems in your strategy, the leading indicators, to give you early awareness of potential issues and the chance to discover that reality may be different than you think it is. If you’ve delegated feedback gathering, you’ll need to delegate notification of outliers along with an assessment of those outliers. You can’t entirely dismiss them, even if they’re outliers, because you need awareness as you aggregate feedback at your level. A few pieces of contradictory feedback, coming from different places, could indicate that your model of the universe needs updates—but it’s entirely possible that nobody at a lower level would have visibility into all the pieces. By seeking out contradictory feedback in a way that balances and contextualized that feedback, your systems will damp feedback without reducing your awareness.

It might seem strange that when adding damping, you also need to add ways to prioritize your awareness of contradictory, outlier feedback. Without those mechanisms, you’d worry about what you were missing out on. You’d stop trusting your feedback dampeners. And you’d be right back where you started, trying to drink from the feedback firehose.

Earlier I talked about the marketing team with the teal turtlenecks. It was fairly common for someone to test a web marketing technique of the more intrusive variety (think pop-ups or modal overlays) and report positive metrics. More sales, higher conversion rate, more email addresses captured, that kind of thing. Naturally, if one pop-up is good, two would be better, right? Even when one person got a bit too excited about adding more intrusive elements, the overall team was good at pointing back to the importance of good design and respecting visitors to the site. The mission and values damped the “more sales through short-term exploitation!” feedback. And by surfacing contradictory feedback (e.g., people dislike pop-ups, not being able to see the actual page content is a pain, etc.), we kept ourselves from diving into a runaway frenzy of adding pop-ups.

Wrapping Up

I don’t have data for this, but I think a lot of people wish they had more feedback so they could say “yes” to the right things with confidence. But let’s flip that around. Without feedback, how can you be brave enough to say “no” to the things that you ought to say “no” to?

It’s true that feedback doesn’t scale. But you need feedback. The world is constantly changing. Things inside your company are constantly changing. Without feedback, your company will fail to respond to changing conditions. That’s, uh, negatively correlated to business success.14

Without access to the unvarnished, contradictory, fast-paced truth of the world around you, you can’t react with grace and agility to the world.15 But with access to the entire unvarnished, contradictory, fast-paced truth of the world around you, you can’t react with grace and agility to the world either.16

That’s why you need systems around you to gather feedback and to damp that feedback so you can handle the truth and respond to reality.

Your goal is to get feedback that lets you sense events early and respond effectively, without overreacting to every piece of feedback. This is a hard problem, because it’s affected by your organization’s culture and personnel.

If your company seems to flail, spiral, oscillate, or just keeps doubling down on the same idea (always citing supportive feedback), maybe the problem isn’t too little feedback. Maybe it’s too much feedback, undamped, without systems to handle it.

And that just might be what’s keeping your company from handling the truth.

- Yes, I know that behaviors, performance, and results are all very much linked. Performance is an outcome of behaviors. Results are an outcome of both behaviors and performance. Separating them lets me make the side point, in this footnote, that feedback can be detailed information about very specific behaviors and incidents (“when you let the corner of your mouth quirk like that, your friend sees it and has to turn his guffaw into a fake cough so neither of you gets detention” – which may or may not be based on a true story from a conversation I had in the past couple days) or aggregated and general (“team, you were all moving way slower than I know you can, and now you’ll need to work twice as hard in the second half to win”). [↩]

- There may be other reasons! Stubbornness, ego, bad decision-making, greed, and many other causes of non-responsiveness may persist in the face of clear feedback. [↩]

- In John Boyd OODA-loop terms, that’s the Observe step and at least part of Orient. Receiving data (or spending a lot of time and effort to gather data)—the Observe step—is useless if it’s not interpreted—the Orient step. In addition, the input needs to affect the mental models used in Orient (either by influencing the choice of appropriate models or by modifying the models). [↩]

- If the idea of lumping the systems concepts of “input” and “feedback” together under the general term of “feedback” feels uncomfortable, realize that the “system” you are looking at (e.g., a person’s behavior, a machine or process, a company’s work, etc.) can be viewed as a subsystem in a larger system. Viewed in this way, any information provided about far-downstream results of behaviors have been fed back through that much larger system. Yes, in other words, zoom out until you’re analyzing the entire universe. Simple, right? [↩]

- Beyond the basic factors that make feedback hard, other complicating factors exist. For example, the Allen Curve shows how distance affects communication (and therefore feedback). Humans are complicated, and messy, and intriguing. [↩]

- Carter’s post was the nudge I needed to turn the note-to-self into an actual post. [↩]

- Many of those folks are great people that I truly enjoyed working with. [↩]

- As the saying goes, the dose makes the poison. I baked some muffins recently. A generous pinch of salt helps them taste good. So why not add a whole handful of salt? [↩]

- Think online reviews! [↩]

- There’s an old joke about a new manager that’s overwhelmed by a stack of resumes. He asks his mentor for guidance. The mentor says, “Here’s what to do. Take the resumes home. Throw the stack of resumes down your basement stairs. Review the ones that land on the top three stairs.” The manager looks confused. “What about the other ones?” The mentor replies, “Throw them in the trash. You don’t want to hire someone unlucky!” [↩]

- The Wikipedia article on damping has some useful illustrations and more explanation. [↩]

- I’m thinking thick, viscous pancake syrup here, not light maple syrup. Maple syrup is delicious, but flows more easily than the imitation stuff. [↩]

- Having a North Star definitely helps keep you moving in a consistent, and potentially useful direction, even if your navigation is generally off. Sorry to those navigating in the southern hemisphere. [↩]

- Citation needed. [↩]

- Imagine, if you will, a basketball game in which the players don’t have access to accurate information about the world. One player sees everything on a five-second delay. Another can only use his sense of touch. Yet another sees everything blurred. Drunk goggles. Hearing blocked and replaced with blaring Taylor Swift songs. Perception that the shot clock is at two seconds every time someone gets the ball. It’d be ridiculously enjoyable to watch, but it wouldn’t be graceful. It definitely wouldn’t be basketball. [↩]

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy explains this fully in the account of the Total Perspective Vortex. Yum, cake! [↩]

Leave a Reply