The YMCA in Marion, Iowa knows more about getting work done than many professional managers.

Recently, this sign went up near the weight machines.1

This sign was posted because, every so often, people will sit at the weight machines for several minutes, not working out. Sometimes they’re resting between sets. But every so often, what started out as a quick phone check during a rest turned into something more absorbing, and five minutes have passed without their realizing.2

Obviously, this gets frustrating for people who want to use the machines to work out.

At times, it’s possible to use a different machine that happens to be free. Other times, you just have one exercise left, and you need to wait for that particular machine.

Sure, you might say, that all makes sense. The sign is a good, common-sense solution to the problem. How does this mean the YMCA knows more about getting work done than managers?

The Efficiency Approach to Maximizing Work

The classic approach to maximizing work is to focus on efficiency, defined approximately as ratio of time spent working to time spent at work. In other words, what percentage of each individual’s time is spent on valuable work tasks.

If I come in, spend half my day playing ping-pong, and the other half cranking through my to-do list, I’m 50% efficient. It’s pretty clear that by doing actual work instead of playing ping-pong, I could get more work done.

And so, the classic3 approach is to watch people, look for times that they’re not busy, and ask them to become busier. In other words, if people are busy doing work, then work must be getting done. Seems obvious, right? Just watch the people to make sure they’re busy.

At the gym, people look busy. They’re at weight machines. Some folks are actively lifting or setting up the machine. Some are resting between sets4. Some are checking off their set or looking up the next exercise in their plan. Maybe one or two have finished wiping their machine down and are just standing around waiting for the next machine to free up. With the exception of the dude that’s been slouched on the leg extension machine scrolling Instagram for the last five minutes, everyone is purposefully occupied doing exercise-related activities. Everyone (again, with the exception of that scrolling dude) has good reasons for being where they are, occupying the machines they’re at.

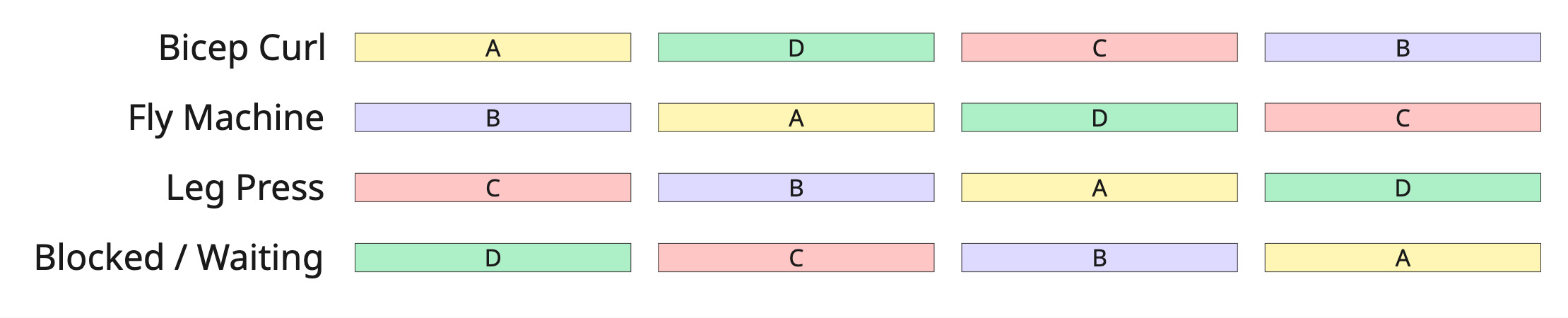

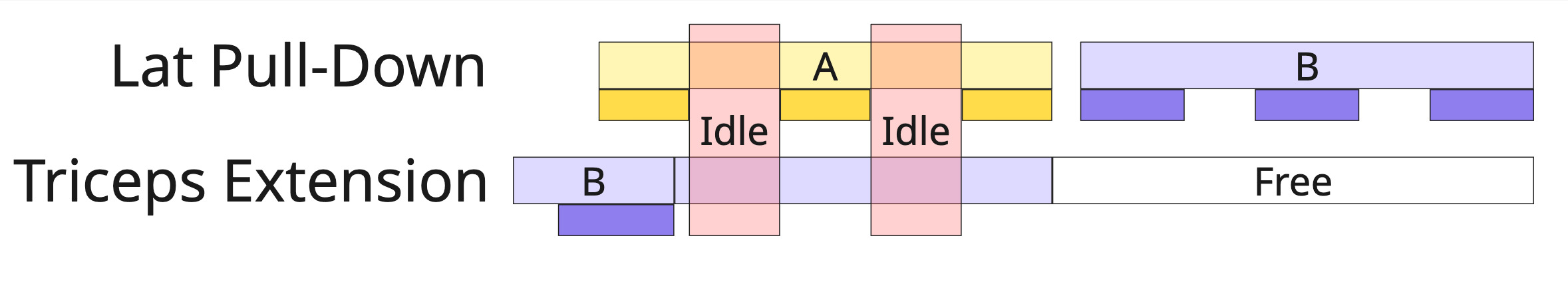

In other words, the people at the weight machines are at close to 100% utilization efficiency.5 Let’s take a look:

In the diagram, there is a bit of empty space as users switch machines. Besides that, the only “unutilized time” is when a user is Blocked/Waiting because there are more people than machines.

You might argue they’re not doing the right activities, or that a central coordinator could help them plan their collective use of machines more efficiently.6

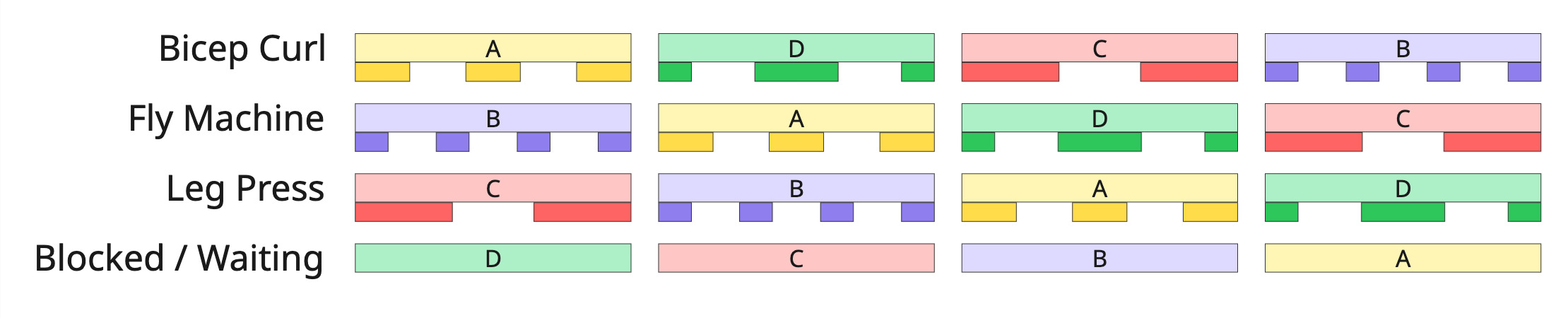

This next diagram shows the active lifting times and rest periods for each user. To me, everything looks pretty reasonable.7

It’s clear that, except for that one scrolling dude (not shown on the diagram), they’re all being reasonably efficient. They lift, they rest, they lift, and they step away from the machine when they’re done using it.

So efficiency does not make a good metric.

So what’s the alternative?

Follow the Work

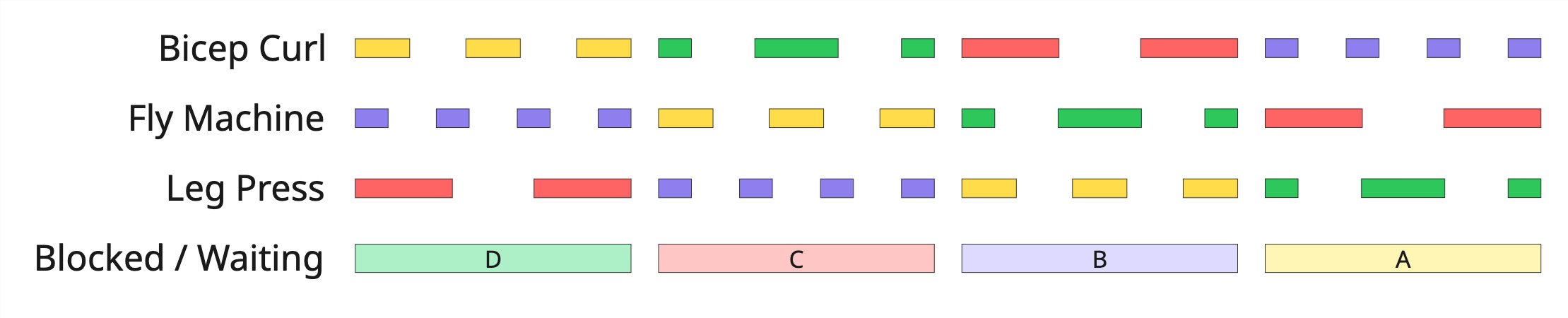

The efficiency approach follows the people to ensure they’re busy. Better to “follow the work”. Instead of checking what people are doing, you check on the progress of work items and whether they’re getting done (or are hung up somewhere, waiting).

If you’ve heard of “value stream analysis“, “value stream mapping“, or “flow metrics“, those tools fit here. But you don’t need all the details of those tools for now.

At the YMCA, using the weight machines is “the work” for those machines. It’s the thing the machines are designed for, and (usually!) the reason people occupy them. Resting between sets, waiting for a machine to free up, checking your next exercise, all those can be done elsewhere. Building muscles, though, is easier if you have a leg press or bicep curl machine.

So let’s look at the scenario above, but focusing on “the work”. The machines have someone occupying them nearly 100% of the time. But each is being set up or actively used for lifting only about 50% of the time. In other words, the machines are 50% idle, or 50% blocked.

Half of the work capacity is blocked, even though the people are at nearly 100% utilization efficiency. Weird, huh? The people are at 100% utilization, but half the work the exercise room is capable of supporting is not happening.

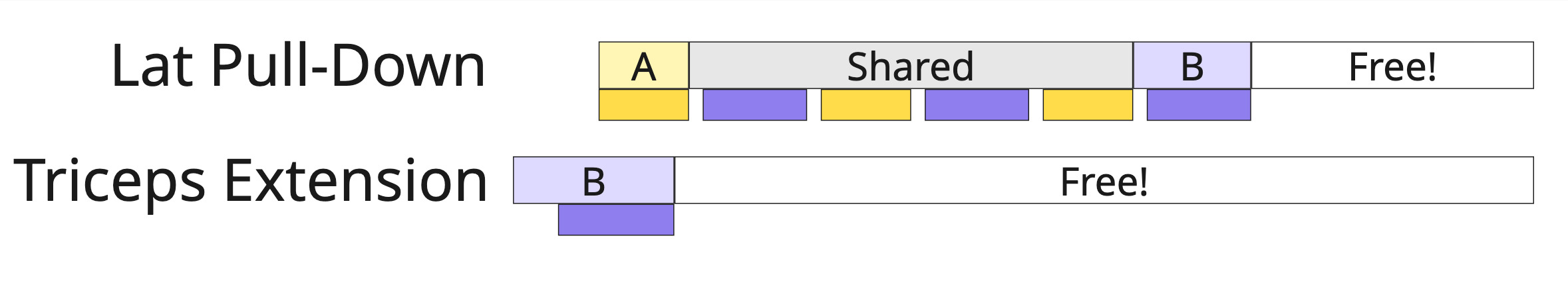

Let’s simplify it a bit more to make it clear. To take a two-machine example, imagine a guy who just finished a set on the lat pull-down machine. He has three sets to go. There’s a guy that just finished his last set of triceps extensions. He needs to get lat pull-downs in for his workout. So he waits, watching the guy at the lat pull-down machine. Without realizing it, the guy resting before his next set of lat pull-downs keeping the triceps extension machine occupied. That means two machines are occupied and idle, versus one machine (triceps extension) being available while the other (lat pull-downs) is being used.

If you’re thinking “isn’t this really just optimizing for utilization efficiency of the machines instead of efficiency of the humans?” you’re exactly right. (At least in this situation; there are difficult situations where it’s not quite so simple.)

The Marion YMCA knows that value is created by allowing people to use the machines for exercise, rather than as uncomfortable chairs. And so, when the machines themselves aren’t busy, value isn’t being created. So it’s better to allow the machines to become busy. Hence the sign, asking users to allow others to work in.8

In other words, the Marion YMCA has one-upped many professional managers. By saying “don’t make the machines wait”, they have optimized for “the work” to get done, not just to “keep the people busy”.

But, I know, you’re not running a gym. Running a gym is easy stuff, right? Nowhere near as complicated as, say, what a tech team does. So let’s look at what these approaches might look like for a software team.

People Efficiency in a Software Team

Imagine you’re managing a software team. You have a half-dozen developers, all reasonably skilled. Like most software teams, you have a mix of of high- and low-priority work. And a mix of high- and low-urgency work.9

Your team is busy, of course. You have plenty of work to do. Any time you ask for status, or pop in to the daily stand-up10, everyone has things going on. They’re all things that you think should be done, too. Nobody’s spending hours playing ping-pong or working on their “when things are slow” projects.

But somehow, the important tasks—even though they get mentioned regularly in status reports and stand-ups—aren’t getting done. They’re not being delivered. The value they’re supposed to bring doesn’t materialize.

There are good reasons for that. Your engineer was waiting on that other team to fix their API, so they’re blocked. That widget got handed off to QA who found a bug and it’ll get fixed right after this other bit of work gets wrapped up. Rob just needs to get an hour with Sue to work out the data formats, and they’re already booked for first thing day after tomorrow.

At least you can comfort yourself knowing there’s a steady stream of smaller, slightly lower-priority tasks that are getting done while your high-priority tasks are blocked. You figure you’re showing you can still deliver, even with all those blockers.

If only you could figure out why the important stuff isn’t getting done. You’re doing a great job of keeping track of what your team is waiting on, so your boss can’t get too grumpy with you.11

Let’s see how that team might look in a “follow the work” world.

“Follow the Work” in a Software Team

One day, the team starts to follow the work. Instead of making sure everyone is busy with something, the team starts with the most important work item. What is that item “doing”? Is it being actively worked on, or just blocked/waiting?12

Aside: This is analogous to looking at the weight machines to see if they are being actively used for weight lifting, passively occupied for rest or plan checks, or have just become a funny-looking chair.

If it’s not being worked on, the team figures out what can be done to move it.13 It’s not enough to say “welp, it’s blocked, let’s move on down the list!” Pooling expertise? Asking for help? Writing the code for a fix to that other team’s API and submitting it for review? Requesting a 5 minute phone call today instead of a scheduled hour-long video call next week? Calling up that VP to ask what they meant by that comment? Asking your boss to get his boss involved?14

Sometimes, it’s genuinely not possible to move an item forward at all. It really does rely on another team to fix something, or a call with a vendor, and they’re completely unavailable to help right now. And if that’s the case, it’s okay. Maybe not ideal, but okay.

Aside: This is analogous to a machine with lots of adjustment options being occupied by someone who is a much different size than you are. It might take way too long to work in with them given all the adjustments that need to be made to switch between the two of you. Or, more straightforwardly, it might be analogous to a machine being out of order.

If there is a way to make progress, or even attempt to make progress, the team pulls as many people to that work as will be productive.

After the team has looked at the most important work item, it’s on to the next most important work item, and so on—until all of the capacity to do work (that is, the people on the team) have been absorbed by the work. Everything beyond can be safely ignored for now, because it’s lower priority than the work your team is now fully absorbed by.15 After all, prioritizing means you must say no, and in this case, the team is saying ‘no’ to trying to get less-important work done—and to the effort to continually shuffle it into the workstream.

The downside of this approach is that you’ll get asked why your team is “wasting time” trying to unblock high-priority items instead of “keeping busy” on items that can be worked now. Actually, no, that’s not the true downside. The downside is that, once you understand, you’ll have to be careful to not sound condescending when explaining.16

The upside of this approach is that you’ll be concentrating your effort on high-priority work. The important things get done—or at least impediments get regularly flagged and help gets requested. When blockers get cleared, the team gets back to making progress immediately.

(Another upside of this approach is that you’ll spend less effort trying to keep people performatively looking busy.)

More of the valuable work gets done. Delivered.

Common Workplace Behavior in the Gym

Yes, this section is going to belabor the point about how truly ineffective our workplace behavior can be. Skip it if you like.

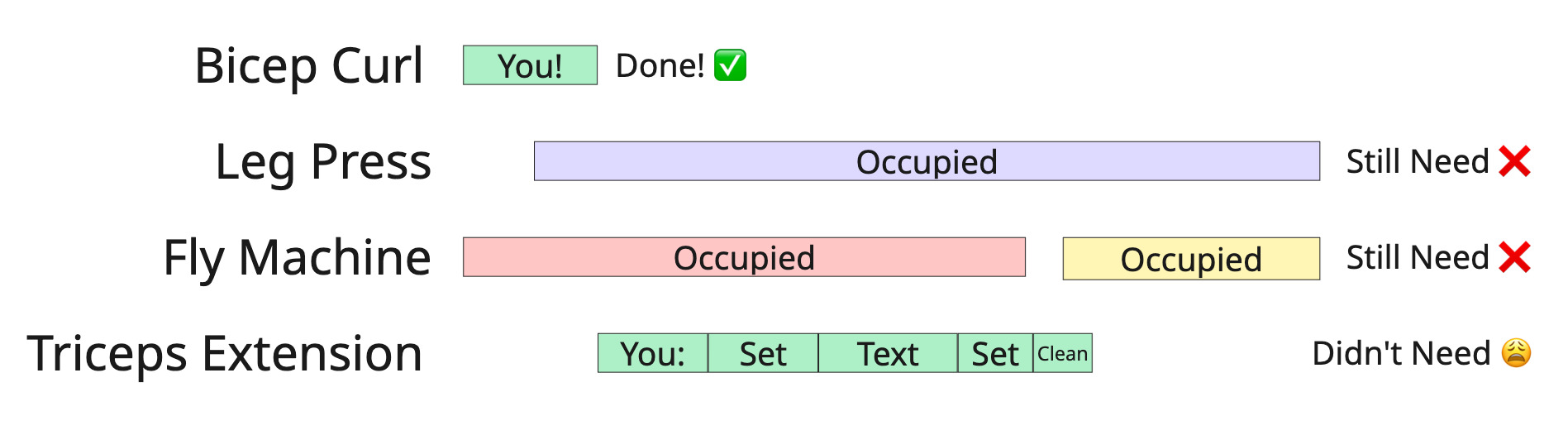

Imagine you’re in the gym. You have one set left at the bicep curl machine (and, if I may say, those arms are looking nice!). You’ve got leg press and a set of flys left after that. Someone just sat down at the leg press, and there’s someone else on the fly machine. You pound out that last set of bicep curls, wipe down the machine, and look around.

Leg press: occupied, user is resting between sets. Fly machine: actively being used.

So you wander over to the tricep extension machine and do a halfhearted set to keep busy. Then you pull out your phone. You send a quick text to your friend to complain about people using the machines you want. You look up to see a set starting at the leg press. Still blocked. So you set your phone aside and start another set of tricep extensions. Halfway through, the fly machine frees up.

You stop your set, hurriedly wipe down the tricep extension machine, but when you turn around you see someone settling in at the fly machine. You missed out on the fly machine! The leg press is still in use—looks like resting between sets again, and annoyingly enough they’re texting. Hmm. The leg curl machine is free…it’s not on today’s workout plan, but it’s better than standing around waiting…right?

(Wrong! And ten minutes later, you’re no closer to finishing up your planned workout—in part, because you wanted to “keep busy” and “do something productive” instead of “just waiting”!)

Watching People

In the gym, if you spend all your time watching people, you don’t get stronger. Plus, it’s creepy.

At work, if you’re spending all your time watching people to make sure they’re busy, it’s only going to make sure they’re working on something. Plus, you’re almost guaranteeing you’re working on the wrong things.17

Don’t be creepy.

Don’t put weird incentives in place that cause people to work on the wrong things.

Wrapping Up

The Marion YMCA knows something that many managers don’t: they know what the value is they are expected to deliver.

The YMCA delivers value when people get the exercise they’re after.

Managers deliver value when valuable work is completed, emphasis on “valuable”. The more valuable the work, the more value delivered when it’s done.18

The YMCA also knows how they deliver that value. The YMCA delivers value by having equipment available to use.

Managers deliver value by causing their team to work on—and finish!—the most valuable work items.19

The YMCA also knows what’s needed to be able to deliver that value. The YMCA knows that besides having working equipment, they need to ask people to accept disruptions to their default behavior so that overall throughput is higher.20

Managers of knowledge workers, your goal isn’t to keep your people busy (efficiency). Your goal is to move the work. To deliver value.

Learn from the YMCA in Marion, Iowa. They didn’t put up a sign that said “Sit at the machines. You need to be busy.”

Instead of watching people to make sure they’re busy, follow the work. Make sure the work is getting done.

You’ll get better results.

Bonus Song!

After writing the word YMCA a few times, my brain spun up the obvious background task.

Young man, there’s no need for a frown, I said

Young man, because your output is down, I said

Young man, don’t wanna look like a clown,

There’s no need to be unhappy!

Young man, you should follow the work,

Young man, don’t be a micromanaging jerk, you can

Try this, and I’m sure you will find

Your team’ll get so much more work done

If you learn from the YMCA!

Interested in spending less time “keeping busy” and more time delivering on priorities? Not quite sure what your next step is? I offer coaching that can help you take that next step with confidence. Tell me what’s going on, and we’ll dig in.

- 🎶 And it opened up my eyes 🎵 … to the theme of this post. [↩]

- We’ll occasionally joke that one of the machines is actually “the texting station”. [↩]

- Taylorist, naive, or “simple, obvious, and wrong”. If this footnote rubs you the wrong way, consider that you may have something to learn from this post. Or that you may have something to teach me. [↩]

- Resting between sets is important. [↩]

- Unless, that is, you want to argue that anything other than active lifting doesn’t count as utilization for the sake of exercise. Now, in fairness, I’m about to make a similar-sounding argument regarding workflows in the next section (it’s actually a much different argument, but at a glance it might sound similar). However, you’ll have a hard time convincing folks at the gym—including me—that active lifting is the only activity that counts for people. Besides, my “similar-sounding argument” changes the thing we’re measuring utilization of. [↩]

- A manager, perhaps? [↩]

- Note that this diagram does not show Instagram-scrolling-guy. He’s not what we’re talking about anyway. [↩]

- There is a bit of inefficiency in adjusting a machine so another user can work in. That overhead is less than the time the machine would be blocked. And if you start looking at how delays can ripple through the entire system, and how the overall time people would need to spend in the gym could increase without working in, that bit of inefficiency is a cost well worth paying. [↩]

- And, of course, priority and urgency aren’t correlated. That’d be silly. [↩]

- I’ll note, gently, Mr. or Ms. Manager, that stand-up is not your chance to get status from your team. If this surprises you, please, drop me a note and let’s talk. [↩]

- Right? The boss can’t get too grumpy, right? (Well, wrong. Your job as a manager is to get the right stuff done. If you’re delivering the wrong stuff, your boss will get grumpy. Yikes.) [↩]

- It’s surprisingly common to find the most important work item (or two, or three) are waiting. It’s blocked waiting on information from someone. Or it was blocked, and now that the information has been received, the engineer “needs” to finish up the task they were working on “to keep busy”. [↩]

- I need to write more about unblocking. For now, I’ll mention that it’s surprising how a little persistent focused effort can unblock something quickly. [↩]

- There’s a very good move available if something appears truly blocked, but that’s going to be difficult for someone just starting to “follow the work”. Once you’ve learned to work hard to unblock high-priority tasks, and become comfortable with an individual or team not being 100% utilized, you’ll be ready for that move. [↩]

- You can always readjust work allocations if priorities change! [↩]

- Condescending means acting like you think you’re better than the other person, often by explaining things the other person already knows like you assume they don’t. [↩]

- Here’s why. Everyone is being pushed to work on something. So when the high priority item gets unblocked, you’re not able to start on it right away. You’ll want to finish what you’re doing, or at least find a good place to pause it. So every minute you spend on that, you’re blocking a high priority item for a lower priority one. There’s more to it, but that’s enough to give you the idea. [↩]

- Almost a tautology, but also true. You can deliver a whole lot of work without delivering any value. (I’ve seen it! You probably have too) [↩]

- Defining value and ranking value of different work items is a whole other discussion. It’s one that’s worth having. For now, allow me to gesture vaguely in the direction of “Cost of Delay”, which provides a consistent economic basis for comparison. [↩]

- It’s the principle of suboptimization at work. [↩]

Leave a Reply