Once upon a time, to practice Ruby on Rails, I wrote a little web-based chore list program.

I needed a way for my kids to know who had to sweep, who had to put away dishes, and who needed to help me rake leaves.1 And a way to mark chores off when they were done.

I built the program around the idea of a daily chore list.

That was exactly how I’d made chore lists by hand. Each day, I’d write a chore list on a fresh sheet of paper. And if someone hadn’t swept the dining room the day before, I’d rewrite “sweep the dining room” onto the new chore list under their name.

It turns out, building the program that way was a terrible idea.

More on that later. For now, let’s take a quick detour to discuss models.

Models matter, a lot.

What’s a Model?

In science, a model is a simplified representation of the real world. Think of the picture your science book probably had of an atom, the one that kind of looked like a solar system. The nucleus was a big ball in the middle, orbited by smaller electron-balls.

In software design, a model is the way concepts are understood, captured, discussed, and represented. Models are often drawn on whiteboards using rectangles and arrows, or more captured formally with UML diagrams.

Science or software, it’s the same concept. A model represents something. It’s not the actual thing. But the model gives you ways of understanding the thing.

As Alfred Korzybski said, “the map is not the territory“. The reality (“the territory”) is detailed and, well, real. The model (“the map”) gives a way to understand and reason about reality.2

Some models are more useful than others. The ancient Greeks imagined all matter was made up of four elements: earth, fire, water, and air. Today, we know of well over a hundred elements (hydrogen, helium, lithium, and so on). Our model(s) of matter let me predict, for example, that potassium (K, element 19) will behave similarly to sodium (Na, element 11). The Greek model wouldn’t easily distinguish between the two, except perhaps to hypothesize that potassium contains more fire than sodium because it reacts more violently with water.

To wrap up our detour through models, a model is a representation of a thing, not the thing itself. The purpose of a model is to help us understand or reason about the thing it represents.

Why My Chore List Model Was Terrible

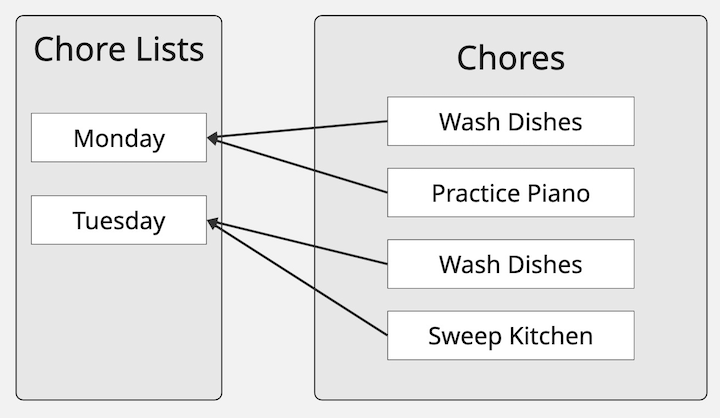

As I said above, my chore list program was built around the idea of a chore list for each day. Monday’s chore list contained chores. Tuesday’s chore list contained different chores.3

The longer I used this program, the more difficulties I ran into.

For example, sometimes, my kids didn’t finish all of their chores. I got tired of manually copying chores from Tuesday’s list to Wednesday’s list, so I added a “carry over” feature. Undone chores got copied to the next day’s list, with an asterisk added to show that it was carried over.

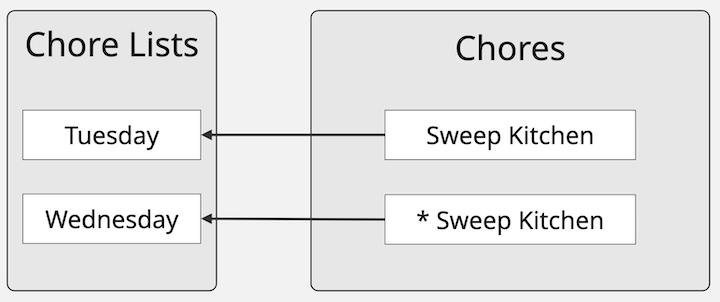

That was all easy enough. But because each chore “belonged” to a list, there was a small problem. Let’s say it’s Tuesday evening, and I want to get Wednesday’s chore list ready. I notice that “Sweep Kitchen” is undone and will need to be carried over.

- I load up Tuesday’s list and click the “Carry Over” button.

- Wednesday’s list is created, including “* Sweep Kitchen”.

- I add more chores to Wednesday’s list.

- Meanwhile, the kid notices they didn’t finish their chore and sweeps the kitchen.

- The kid checks off Tuesday’s “Sweep Kitchen” chore.

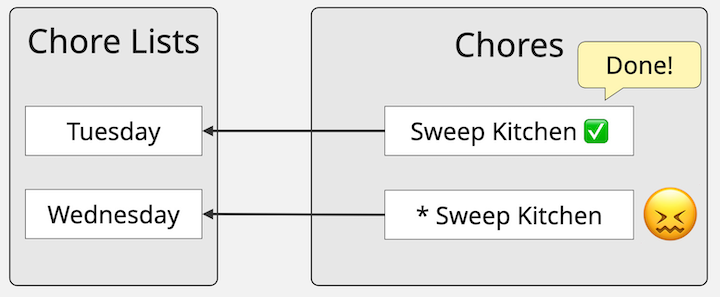

- ❌ Wednesday’s chore for “* Sweep Kitchen” remains. ❌

That created inaccuracies, annoyance, and frustration.

There was similar frustration if I started creating a chore list for Wednesday, not realizing chores weren’t done from Tuesday. If I didn’t click the “Carry Over” button, undone chores would never be seen again.4 At least once, someone got away with not doing chores because undone chores didn’t automatically show up the next day.

Sometimes, I wanted to plan ahead. Spring cleaning, fall garage clean-out, preparing for a family visit—all predictable events for which it’d be nice to enter a list of chores ahead of time. Unfortunately, if I created a chore list for Saturday, I’d have to do manual chore carry-over.

Sure, I could write some code to make that all work, probably. But it’d be way harder than it felt like it should be. I’d have to check for the existence of lists on a given date, compare chore names and assignments while handling carry-over asterisks… Again, not impossible. But finicky, error prone, and felt wrong somehow. Like the model didn’t represent reality—or at least how I thought about reality.

Besides that, there were some things that would be really hard or potentially impossible to write code to handle. A nice feature to have would be some statistics on how long it takes each kid to do their chores, and which chores are most ignored. Remember how each chore list contains its own unique chores? “Sweep Kitchen” on Tuesday and “* Sweep Kitchen” on Wednesday aren’t at all connected in the database. So doing those statistics would be, at the very best, error-prone and difficult.

As a basic chore list, it worked fine.

But adding capabilities was difficult, all because I chose the wrong model.

My model was quick to build, made basic sense, and mapped nicely onto the way I’d made chore lists on paper.

It turns out that I ended up with a model that was mostly accidental because I had originally made chore lists on paper. Having a chore list per day makes sense, if you’re using paper, and need a fresh “view” (a clean sheet of paper) every day. On paper, there’s not really a chore “entity” to connect to. It’s just ink, and if you want a chore to show up the next day, you need to rewrite it. So the model I built represented the limitations of paper more than how I really thought about chores.

Oops.

I don’t want “Tuesday’s List – Sweep Kitchen” done. I want to assign sweeping the kitchen on Tuesday. And I want sweeping the kitchen to stay assigned until the kitchen has been properly swept.

I don’t want Practice Piano and * Practice Piano and ** Practice Piano to show up on a chore list if practicing hasn’t happened in a few days.5

I just want one version to show up. (Probably the one that says “hey, you have been neglecting this for a bit”. I think.)

The Better Model

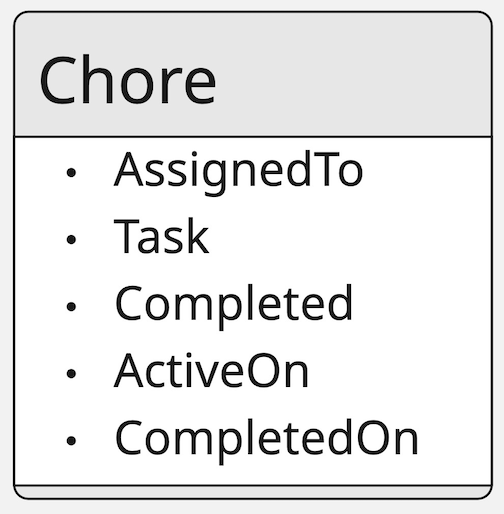

You might be asking what a better model is. Well, I’m in the process of rewriting the chore list program with the individual chore as the fundamental unit.6

A chore has all the basic attributes you’d expect (who it’s assigned to, what it is, whether it’s done), plus two dates: the date it was completed and the date it becomes active.

The Active date lets me stage a chore for the future.

The Completed date lets me know when it’s done.

And that means a “chore list” is a virtual concept, not a database entity.7 Instead, the list of chores for any given date is the list of chores that

- became active on that date or earlier

- are either incomplete or were completed on that date8

Cost of Bad Model

What’s the cost of a bad model?

Bad models use more time, limit flexibility, create frustration, lead to bugs, add complexity, sap motivation… Bad models get in the way and slow work down in many different, and often subtle, ways.

Until I decided to just rewrite the chore list program, I’d been putting off making small changes to it. Each change would mean lots of tedious follow-up changes. None of it was hard, but there was so much of it and it all felt entirely unnecessary.

Alan Kay is quoted as saying “Simple things should be simple, complex things should be possible.” Larry Wall adapted the quote as “Easy things should be easy, and hard things should be possible.”

Bad models do the reverse. They make simple things hard, and hard things impossible.9

Avoiding Bad Models

To wrap this up, allow me to suggest that you avoid bad models.

The end!

Okay, avoiding bad models is easier said than done. Obviously, a bad model bit me. And this project is not the only time that’s happened.

Part of the reason I got bit by a bad model when writing my chore list program is that I wanted to “just get it done”. I wanted to stop making new chore lists on paper every day. I rushed into something that “worked”.

What I didn’t do—and what I recommend—is taking a bit of time up front to think, just a little. Understand the problem you’re trying to solve.

As a one-for-one replacement for writing chore lists on paper, my original chore list program is excellent. The model is exactly correct. But as a solution for managing chores for my kids, the model is wrong. I didn’t start by thinking about the real problem I was trying to solve.10

Once you’ve understood the problem you’re trying to solve, take some time to think about the problem.11 You’re not trying to understand the solution, not yet. I call this part “walking around inside the problem”. As I walk around inside the problem, I get ideas of what the problem and its solution might look like. But until I understand the problem, I can’t be sure a solution works—I can’t solve it.

After understanding the problem, do some quick, high-level sketches of a model, and how you might solve the problem using that model. Tweak the solution and model as needed during this part. “Okay, so I have a Chore. If it doesn’t get done, how will I know to show it on tomorrow’s list? Oh, I can check whether it’s completed. Cool. But what if it’s not supposed to start until next week? Ah, I’ll need to…”

If the solutions feel more difficult than they need to be, that’s a sign the model is wrong. Go back and try a different model. You’re already thinking about the problem, and it’ll never be easier to pick a new model.

Now, it’s possible you won’t find flaws in your model until you’ve gotten deep into your project. Sometimes you have to build—and use—a bad model to get to the right one. No judgment here, it happens to us all.12 But don’t let the possibility of ending up with the wrong model make you think that spending some time up front exploring possible models is a waste of time. It’s not.13

If you choose the right model, solutions become so much easier.14

The first model that occurs to you may not be the right one. Test your models and find the right model. It’s worth the effort.

- Making kids do chores is a good thing. One of a very long list of benefits is that it helps them understand they have the ability to contribute to the world in a meaningful way. [↩]

- Maps help by being smaller than the real territory. (A full-scale map would be useless in most situations!) Other models help by giving names to behaviors or entities—or by identifying nouns and the verbs the nouns do. [↩]

- Chores were different entities in the database, tied to Chore List entities. Specifically, each chore was a row in the Chore table, with a foreign key to an entry in the ChoreList table. The ChoreList was associated with a date. [↩]

- Undone chores would almost certainly not be remembered by the kids. And if they did remember, they’d certainly not remind me! [↩]

- I added a nice feature that I called “Everyday Chores”. I got tired of typing a new practice reminder into the chore list every day. So now things like “Practice Piano” get added automatically every day. [↩]

- In C#, using Blazor. Diving into frameworks and learning is fun. [↩]

- Very likely there won’t even be any code that represents a chore list entity either. There will be a view representing a chore list, of course, but it’ll be fed a collection of chores that answer the question “what chores need (or needed) to be done today?” [↩]

- Technically, that on that date or in the future. If I’m looking at lists for dates in the past, “the future” could very well also be in the past. [↩]

- This is also how kids are apt to spin their chores. “Put away my clean laundry? Impossible! Maybe with a thousand servants and a hundred years, I could begin to make a dent in that task. On my own? Sir, it cannot be done!” Clearly, they have low affinity for chores. [↩]

- And that’s okay. It happens. And it’s a reminder that even with plenty of experience and “knowing better”, humans make mistakes. Even me. [↩]

- Get to understand the problem in its own terms. Understand the “shape” of the problem, and the moving parts involved. [↩]

- Fred Brooks wrote “plan to throw one away; you will, anyhow.” The act of building leads to learning. It’s very unlikely you’ll get everything right on your first try. However, build the first one with care, rather than as a throwaway, so you’ll really be able to learn from it. It’d be a shame to have to build two to throw away. [↩]

- Even this post took some exploration to end in the shape it did. The original version had a different emphasis, a very different flow, and was probably much less useful to read. When I got stuck trying to figure out a transition, I realized I needed to re-shape the post—that is, to model it differently. Doing so made the post better—and some of the ideas I generated with my initial “wrong model” also made the final post better. [↩]

- Long ago, I was working with a small team to model railroad track for train control systems (I should write about this, sometime, by the way!). Track has “switches” that allow trains to move from one track to another. The vast majority of switches are vaguely Y-shaped: two tracks combine into one (or from the other side, one track splits into two). There are three-way switches out there as well, where one track splits into three. Switches are often located at “control points”, with signals a short distance from the switch. That’s a lot of complexity to cram into a model, especially if it needs to be processed by a relatively low-powered processor on a train. We eventually realized that all of our problems disappeared if we modeled all switches as two-way switches at a single point (ignoring control point boundaries, signals, turnout track, etc.). We traded lots of big annoying problems for the very small problem of representing three-way switches (mostly in yards, where our system wouldn’t operate anyway—but when we needed to, they could be modeled as two back-to-back two way switches, with only a tiny increase in the complexity of our navigation code). It felt like a math problem when all the complex terms cancel out. [↩]

Leave a Reply